L ondres, Inglaterra. Martes 28 de marzo de 2006. (EFE) Ian Hamilton Finlay, considerado como uno de los más destacados escultores británicos, falleció a la edad de 80 años, informó hoy la prensa británica.

Finlay, cuyas obras figuran en numerosos museos de arte contemporáneo del mundo, murió ayer, lunes, en una residencia para ancianos de Escocia tras una larga enfermedad.

El artista había vivido desde 1966 en la granja de Stonypath, en las colinas de Pentland, al suroeste de Edimburgo, donde creó su pequeño jardín, que llamó Pequeña Esparta, según destacan los periódicos The Guardian y de Daily Telegraph.

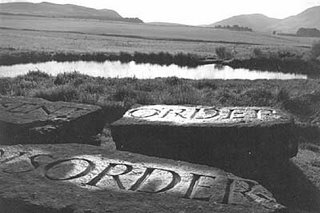

Ese espacio privilegiado de su granja combinaba paisaje, árboles, plantas, esculturas neoclásicas y poemas, en una especie de Gesamtkunswerk u obra total.

Cada superficie, desde los bancos hasta las piedras y obeliscos, llevaba inscritos textos filosóficos o líricos suyos.

Nacido en 1925 en Nasay (Bahamas) , Finlay se estableció en 1950 en la capital escocesa.

El año pasado, con motivo de su ochenta aniversario, Finlay fue objeto de un gran homenaje en el Jardín Real Botánico de Edimburgo.

La Pequeña Esparta es desde 2005 propiedad de una organización con fines benéficos, que se ha propuesto como objetivo proteger el jardín.

Breve semblanza por Prudence Carlson

The art of Ian Hamilton Finlay is unusual for encompassing a variety of different media and discourses. Poetry, philosophy, history, gardening and landscape design are among the genres of expression through which his work moves, and his activities have assumed concrete form in cards, books, prints, inscribed stone or wood sculptures, room installations and fully realised garden environments.

Common to all of Finlay's diverse production is the inscription of language - words, invented or borrowed phrases and other semiotic devices - onto real objects and thus into the world. That language inhabits, for Finlay, a material or real dimension gives rise to the two seemingly opposed but signal characteristics of his work.

On the one hand, Finlay, beginning with with his early experiments with concrete poetry, has always been acutely sensitive to the formalist concerns (colour, shape, scale, texture, composition) of literary and artistic modernism. On the other hand, Finlay, a committed poet and student of classical philosophy, has also always recognised the power of language and art to shape our perceptions of the world and even to incite us to action. Fused in his work is thus a certain formalist purity and an insistent polemical edge, "the terse economy of concrete poetry and the elegant [and speaking] simplicity of the classical inscription." Formalist devices are themselves shown to be never without meaning, and they are ingeniously deployed by Finlay to arm his works with an ever more evocative content.

The movement of words and language into the world has been most fully realised by Finlay in his now famous garden, Little Sparta, set in the windswept Pentland Hills of southern Scotland. Begun in 1966 when Finlay relocated with his family to the site, an abandoned farm, Little Sparta is a deliberate correction of the modern sculpture garden through its maker's revisiting the Neoclassical tradition of the garden as a place provocative of poetic, philosophic and even political thought.

At every turn along Little Sparta's paths or in its glades, language - here plaintively, there aggressively - ambushes the visitor. Plaques, benches, headstones, obelisks, planters, bridges and tree-column bases all carry words or other signage; and this language, in relation to the objects upon which it is inscribed and the landscape within which it is sited, functions metaphorically to conjure up an ideal and radical space, a space of the mind beyond sight or touch. The garden historian John Dixon Hunt has written that "the ideal gardener is a poet." Finlay, in an astonishingly explicit way, is this ideal gardener, having made of his Little Sparta a sustained as well as highly sensuous poem.

The garden of Little Sparta has been described as "the epicentre of [Finlay's] cultural production," from which his other works in a sense emanate. With its far-ranging allusions to pre-Socratic philosophy and Ovidian metamorphoses, to the art of Poussin and poetry of Vaughan, to the imagery adopted by the shapers of Revolutionary France, to WWII sea battles and contemporary Scottish fishing craft, Little Sparta itself stands as a single grand metaphor for no less than Western Culture.

It, like Finlay's other works, both chronicles and re-enacts the complex, contradictory relation between Culture and Nature, between the cultivated and the wild (for Nature only becomes intelligible to us when ordered through cultural constructs that necessarily belie Nature's essential, untamed "naturalness"). To re-invoke Nature and its real raw power - and to re-establish poetry's and art's relevance in the world - Little Sparta has been made rife with images not only of invincible Antique gods but also of deadly modern warships, our nearest symbols of sublimity and terror.

At the heart of all the varied materials and forms through which Finlay's invention flows are his prints, cards, booklets and "proposals." These works -- as works on paper -- bear an especially intimate connection to Finlay's activity as a poet. Meaning, in the purely non-literal or figurative sense, is more obvious as such in Finlay's paper works than in his three-dimensional pieces which often have an irresistible physical presence. This meaning, which can be suggestively open-ended, is arrived at through metaphor -- i.e., through the coupling, on a single page, of unlike terms which are brought to behave as "multivalent" pointers, or as shifting invocatory signs.

To allow his own and others' experimentation with elements of language as signs - as both graphic and connotative/poetic devices - Finlay founded in 1964, along with Jessie McGuffie Sheeler, the Wild Hawthorn Press. Finlay's production through the press has been unceasing and prolific. The press has served as a nursery of ideas for Finlay's sculptural and garden works. It is also Little Sparta's publishing, or disseminating, arm. The themes engaged, so often with incisive wit, at Little Sparta are ones usually first examined and then re-examined in Wild Hawthorn imprints.

Among these themes are the relation between Nature and Culture as symbolised in gardens and the activity of gardening; the Sea as an instance of Nature's sheer power and problematic beauty; (Neo)Classicism, with its attendant aesthetics, philosophy and politics, as the defining type of Western culture; and the French Revolution as an especially rich instance of Neoclassical thought and forms married to pastoral (gardening) imagery.

A fellow poet has written of Finlay's works on paper the following: "The model of order is ... [the] pages of a folding card or a flimsy booklet, produced with care and diligent collaboration to give the reader a shock not of recognition but of cognition, which is much harder and much more valuable." Each of Finlay's works, whether on paper or in some other, very different medium, offers that "shock ... of cognition".