El artista en sus últimos días.

El artista en sus últimos días.C iudad Juárez, Chihuahua. 23 de agosto de 2006 (Ranchonews).- En la edición correspondiente al mes de agosto de la revista El Paso Scene, ocupa el principal trabajo un texto Lisa Kay Tate titulado «The Legacy of Luis Jimenez» (El legado de Luis Jiménez) sobre el artista paseño que murió recientemente en un accidente ocurrido en su estudio.

A continuación reproducimos un fragmento del texto:

On June 13, artist and native El Pasoan Luis Jimenez, 65, was crushed and killed in his home studio, a converted schoolhouse in Hondo, N.M., the victim of an accident involving his latest work.

Area media immediately reported comments and condolences from fellow artists, friends and collectors of Jimenez’s works nationwide, all mourning the passing of the artist and his legacy. He was called “groundbreaking,” “influential,” “a legend” and “genuine” by such well-known names in El Paso art as Gaspar Enriquez, Gabriel Gaytán and James Drake. New Mexico Gov. Bill Richardson even issued an executive order for flags across the state to be flown half-mast in the artist’s honor.

However, Jimenez’s work wasn’t always received well locally, and even landmark works such as “Plaza de los Lagartos” at San Jacinto Plaza, “End of the Trail with Electric Sunset” at the UTEP Library and “Vaquero” at the El Paso Museum of Art were met with equal amounts of praise and condemnation when first introduced to their permanent homes.

One of Jimenez’s close friends, photographer Bruce Berman, described why Jimenez’s work was always met with such strong reaction.

“He was chaotic, and he was precise,” he said. “A really fine combination.”

Representing the Sun City

Jimenez was born to Mexican immigrants in 1940 and learned much of his artistry skills while working as the potential heir in his father’s sign shop and while visiting his grandparents in México City, where he gained an appreciation for 20th-century muralists.

El joven Jiménez.

El joven Jiménez.He attended college at the University of Texas at El Paso and UT Austin, and also studied in México City. With a degree in architecture, he went to New York City in the 1960s and worked for a nonprofit group organizing dances in impoverished Latino neighborhoods. Ironically, it was in New York where the artist who became such a symbol of the borderland culture first began to exhibit his drawings and sculptures. He did shows at the prestigious Graham Gallery in 1969 and 1970, followed by a show at OK Harris Works in 1972.

By 1977, Jimenez had shows in New Orleans, Houston, Long Beach, San Antonio and Santa Fe, and even at Las Cruces’ New Mexico State University, but was not featured in a major El Paso exhibit until 1982, when he was featured at UTEP’s Fox Fine Arts Main Gallery.

Jimenez’s work had an instant impact on Adair Margo, and she remembered purchasing two lithographs from him, “Vaquero” (the influence for the sculpture of the same name) and “Southwest Pieta,” the same day she saw them. Margo would later open the Adair Margo Gallery and become the area representative for Jimenez’s work.

“Luis Jimenez is the first artist whose work I bought,” Margo said in a recent El Paso Times interview. “I’ll never forget going to his dad’s neon sign shop and meeting him, seeing how he worked with those big fiberglass molds.”

It was also a Jimenez work that became Margo’s first sale, leading her down her own path as an internationally respected art dealer. The piece was none other than Jimenez’s “End of the Trail with Electric Sunset.” The fiberglass sculpture of the well-known western image of a Native American rider accented by a sunset of bright-colored light bulbs was purchased by a California collector who gave it to the UTEP Library. At the time, some called the piece a wonderful representation of the vibrancy of Chicano art, while others likened it to a carnival attraction.

Man on Fire, 1969-70. Fiberglass and epoxy resin coating, 89 x 60 x 16"

Margo said that one thing Jimenez had in common with his father, Luis Sr., was creating works with longevity. His father’s creations were part of the El Paso business landscape for many years and included the horse head for Bronco Drive-In, the Red Rooster Bowling Alley sign and the still-standing white polar bear on Wyoming. When the Red Rooster sign was finally taken down, Jimenez erected it in front of his Hondo home studio, a tribute to his love for his father and his own large-scale pieces.

“Evidence of his father’s work can still be found all over El Paso,” Margo said.

El Paso Museum of Art Director Becky Duval Reese said it is Jimenez who gives first-time museum visitors their initial peek at El Paso’s artistic and cultural heritage, as his sculpture “Vaquero” adorns the Arts Festival Plaza at the museum’s entrance.

“‘Vaquero’ is a sculpture that reminds us that the first cowboys were Hispanics, yet that fact is rarely discussed in Westerns or in Hollywood films,” Reese said. “Because Luis was born and raised in El Paso, and because he is internationally known, it seemed fitting to have one of his major sculptures greet visitors as they enter the museum.”

The piece is the first impression visitors have of the museum and often one of the most lasting ones.

“I often observed visitors posing to have their pictures made standing in front of the ‘Vaquero,’” she said. “The work has become a signifier/identifier for the art museum.”

According to Reese, like “Vaquero,” other pieces of Jimenez’s most famous works, such as “Southwest Pieta,” “Sodbuster,” and the “Honky Tonk” series, are some of the more controversial pieces of Hispanic art created.

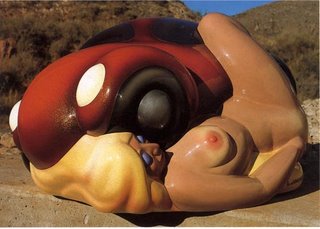

The American Dream, 1967-69. Fiberglass and epoxy resin, 20 x 31 x 35 1/2"

The American Dream, 1967-69. Fiberglass and epoxy resin, 20 x 31 x 35 1/2"“In my observation, people either loved his art or disliked it,” Reese said. “The work is big, colorful, exaggerated, ‘not pretty’ and the messages are in your face.”

Even the celebrated “Vaquero” once came under fire when residents of a primarily Hispanic neighborhood near Houston’s Moody Park, where the statue stood for more than 10 years, complained that the gun-toting figure sent the “wrong message” about Hispanics. Jimenez was quick to kindle the fire of controversy through a series of public forums.

“I consider myself a member of the Hispanic community in Texas,” Jimenez said. “It’s my heritage. And I see ‘Vaquero’ as retrieving part of the heritage that we lost. The cowboy is not a Hollywood invention. The vaquero is a real historical figure.”

Reese said Jimenez’s Mexican ancestry and American roots were able to help him to “understand life from two points of view.” He drew on memories from his childhood observations and stories of his immigrant father and grandparents in order to find a way to bring dignity to their hard-working lives, as well as the lives of the disenfranchised. She said Jimenez has commented on his work by referencing regional writers like William Faulkner, as well as his own socio/political statements.

“Every one of them focused on a very particular isolated situation that they knew well, and in doing so, spoke also to broader issues,” Jimenez has said of his work.

El Paso artist Susie Davidoff, longtime friend of Jimenez, said that one piece that Jimenez felt was very important was his “Border Crossing,” a depiction of an undocumented immigrant crossing the river while supporting a loved one on his shoulders.

SI DESEA LEER EL TEXTO COMPLETO PULSE ESTE ENLACE

El Paso Scene Feature Article